The fifth and last story from the future of the Congo Basin is much more in the present than previous ones, and brings us from Bamenda to Limbe, in Cameroon

I stood by the shores, at the far end of Limbe, and feared moving close to the raging waves. As if they were pursuing a furious intruder, they pushed hard coastward with piles of plastics and industrial waste, some local, others international, and deposited them at the banks. Then gently, they disappeared to reappear several times, performing the same ritual, until a huge hip of waste lay where previously there was nothing. How could such an action be performed repeatedly with ever the same efficiency without any form or degree of consciousness? How was that even possible? Was the sea consciously cleaning herself? The way it happened, it seemed there were some invisible hands, sweeping the dirt out. I looked at the world around me and it was a mystery that scared my inquisitive mind. I was in Limbe, one of Anglophone Cameroon’s popular coastal cities.

It all started with a night’s journey from the high hills of the Bamenda grassfields through busy bus stops spotted here and there along the road with different hawkers. There were those selling soya and the ones selling roasted fish. Everyone was shouting “soya” “soya“, “burning fish“, “bitter kola“, and forcing their way into the car. And this happened every time the driver stopped either to pay toll fee or bribe a police officer or smoke his cigarette. Other times, he smoked while driving, shouting at the bus conductor to collect the transport fare of passengers they picked by the road side and give him. From all indications, they were all suspicious of each other as keepers of the booty.

There were passengers in the seventy-seater bus who could not wait for the next bus stop. Whether it was bread or miondo or anything chewable, they bought everything. Those drinking juice from cans and plastic containers had the typical use-and-dump instinct in common. While those eating different things from plastic papers dispose of the papers just where they were sitting, those drinking juice would get up gently and stagger to the window while the car moved. If they were close to where a window could be opened, they would draw it wide and then fling the container outside. The behaviour was so common that I began to wonder if anyone cared at all about the ripple effects of such actions. Nursing mothers with disposable napkins, and those vomiting in papers due to car allergies, threw the filth through the windows into the rivers or bushes. Coupled with the cabbages and green spices that people had bought from Santa and packed above their heads in the lockers, the odour in the car was a complex gas that lacked qualification.

When we reached untarred parts of the road, the windows of the car would be completely locked up to block dust smoke from entering into the car. When people say that there is still another hell after this life, I wonder what exactly it would mean for someone who has outlived the cruelty of nasty existence, because there is also earth fire. Even in the rainy season, when it does not rain for two or three days, the road becomes dusty, given the number of cars that ply the road daily. As no one suffocated, it was only the grace of God.

There were provisional bamboo chairs and empty twenty-litre containers for extra passengers that would be picked on the road haphazardly. The chairs and containers would be put on the passageway such that it was impossible to stretch a leg or arm without provoking a neighbour. One wouId have been helplessly busy throughout the journey if they took upon themselves to resolve all the quarrels and name-callings in the car. Some passengers were just rude for nothing. If someone smiled at them, they would frown; if they were offered a thing by the neighbour, they would not refuse, but it would be received grudgingly as if someone just returned to them what was theirs. When the passageway was full, the bus conductor would take more people to stand by the staircase. Some would enter without being told that they would have to stand. As long as the bus would not stop just for them to step down, they would figure out where to hang their heads and place their feet until another passenger alighted before they would have where to sit. I wondered how people would care about their environment when they did not even care about each other. How could one take it seriously that populating the earth with plastics was anathema, when they steppped on others’ toes and added insults and quarrels to the hurt without remorse?

My neighbour opened his mouth widely and yawned carelessly. His teeth were chucked with decaying particles of fish that he had eaten since Santa and started sleeping. You can imagine the combination of such assorted breaths in a poorly ventilated and overcrowded car. Parents who paid for one seat and came in with two children had the highest trouble in the car. If they were not fighting with their neighbours, they were busy struggling to find the easiest sitting position.

Before we reached Limbe, I had seen all sorts of drama on the road. But at least, it was of great relief to breathe fresh air once more into my constipated organs. We passed by the grave of Alfred Saker whom we learnt in primary school was one of the first missionaries to come to Cameroon. But I could not resist the sight of the broad water body any longer.

That was when I stood by the shores, at the far end of Limbe, afraid to move close to the raging waves. The waves behaved as if they were pursuing a furious intruder, pushing hard coastward with piles of plastics and industrial waste deposited by some locals and non-locals at the banks. Then gently, the waves would disappear only to reappear several times, performing the same ritual, until a huge heap of waste lay where previously there was nothing. And this made me wonder how such actions would be performed repeatedly with ever the same efficiency without any form or degree of consciousness. I wondered how that was even possible. Was the sea consciously cleaning herself? The way it happened, it seemed there were some invisible hands, sweeping the dirt out of the Atlantic Ocean. As I looked at the world around me, it became a mystery that scared my inquisitive mind.

And I wished I could live a quiet life, asking no question, mindless as the trees in the forest, unaware of the future. But what can one do with this burden called mind, whose essence is inquiry? It might have been better to be a plant or an animal or any other thing apart from a human being. Here I am, trapped in this frame. Who even knows the scars of other existents?

How do physical bodies deemed inanimate and vegetative contain a force that attracts or repels from a distance? Are such occult forces also purposeless, thoughtless and mechanical? Who says they cannot fight back? Is this lingering karma also a product of chance?

Oh, thou who art beyond the farthest,

Hidden beneath the deepest depths,

Should we be comforted at all,

That you record with attention

The quicksand of human babbling?

Oh, hidden cloud,

Force of incessant seduction,

Muse charm of superhuman elevation,

Should we be sad and desolate?

Is there a cure to this encroaching mortality? Mortality beyond humanity.

Have we hastened to complete what you did not start? When it all began,

Like the clap of sudden thunder,

Pulling us deep into the memory of time,

When we followed light from burning bamboo splinters

To termite nests and cricket holes,

And tracked whistles of joy at hill tops

In the hunt for beetles and green grasshoppers,

Enlivened by cold nights, ever fresh verdure,

We couldn’t imagine it turning this terrifying soonl

All we have are memories of the symphonic blend of nature’s forces.

When we scrambled over mandarin fruits on tree branches.

Diving green, red. yellow beetles clutched on iroko elephant grass stems.

Falling on a multitude of fruits in the bushes,

Alert every blessed morning.

Of the partridges’ announcement of a sunny day.

In joyful cackles as they patrolled fallowed green fields,

Or the fowls’ foresight mourning of a rainy day,

As I speak – naked, sweating blood

In green-deserted cities –

We’ve waited in vain, in the soaring malice

For the sight of a single beetle,

Farting different mixtures

From the rubber boxes straddled on our bocks

To the earth, our nurturing ground.

Tell me, what else is mortality?

As these thoughts ran through my mind, a light sleep took over me.

I saw the future. Yes. It was so clear I could not sustain any doubt about it. I was undergoing the same journey from Bamenda to Limbe.

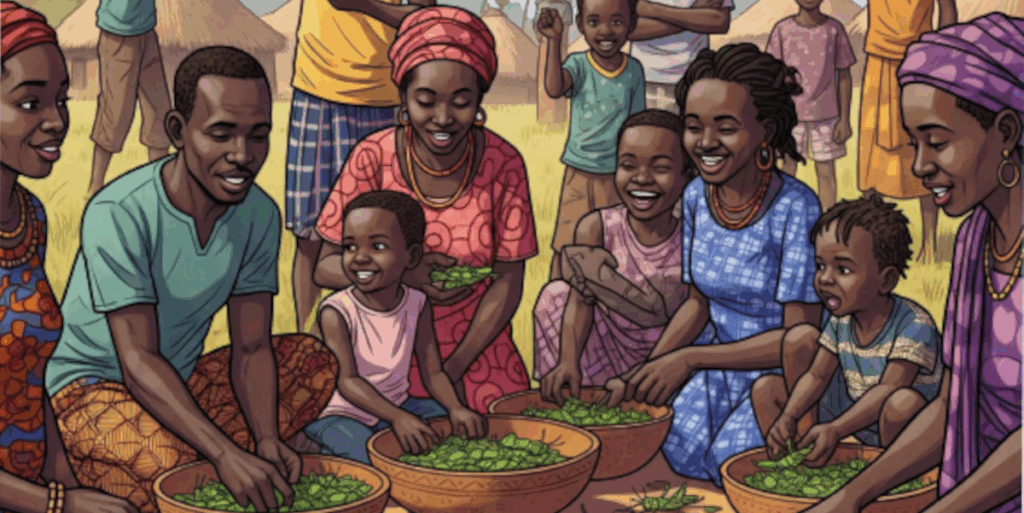

All travel agencies had a sanitary officer in addition to the bus conductor. There was a dustbin in every car and whoever ate anything had where to dispose of the dirt in the car. There were waste disposal spots at particular spots on the road. At any of such spots, the car stopped and the sanitary officer went out to dispose of the dirt professionally, perishables separately from the imperishable. All companies using imperishable products were ordered by law to contribute a percentage of their income to sponsor the recycling company that took care of the waste they produced. It was a completely different world, a green and clean world.

Gradually, our people became deeply environmentally conscious and it was good going to Limbe. There were no more dirt deposits at the coast.

I chucked up from sleep to face my reality. Sad! How were we going to live in the world of my dream? How was it going to happen? That was how I left for a leisure trip, and returned with a huge assignment! Indeed, the future has lots of surprises for each person!

Stanislaus Fomutar

This text has been written after two participatory foresight workshops on #CongoBasinFutures and #RoyalAnimalsFutures in Yaoundé, Cameroon, on Saturday 7 September 2024. It has been edited by Nsah Mala and published by Next Generation Foresight Practitionners.